Margaret Heckler ’56 was the unwanted child of poor Irish immigrants who rose to the highest halls of power. Of her life, she would declare: “I was always in touch with my destiny.”

It’s an enigmatic statement if there ever was one. What she may have meant by it dwells, perhaps, within her private papers, which are archived at Boston College’s Burns Library. A few years before Heckler died, however, some seventy or so boxes were still in storage in the custody of her family. Wanting to know her mother-in-law’s story while she was still able to tell it, Kimberly Heckler started wading through them. “Some of the stuff in there were old pens or dry curlers, but then I would see pieces from Richard Nixon saying, ‘please don’t turn against me here.’ I would see things from LBJ saying ‘because of you, women are entering the military,’” Kimberly Heckler said. “And then I would look and find out that she was the author of the law that gave women credit and credit cards in their own name in 1974.” Clues like these led Kimberly Heckler to realize, “I was in the presence of greatness. And I hadn’t even recognized that she was, in fact, an American heroine, and her story had not been told.”

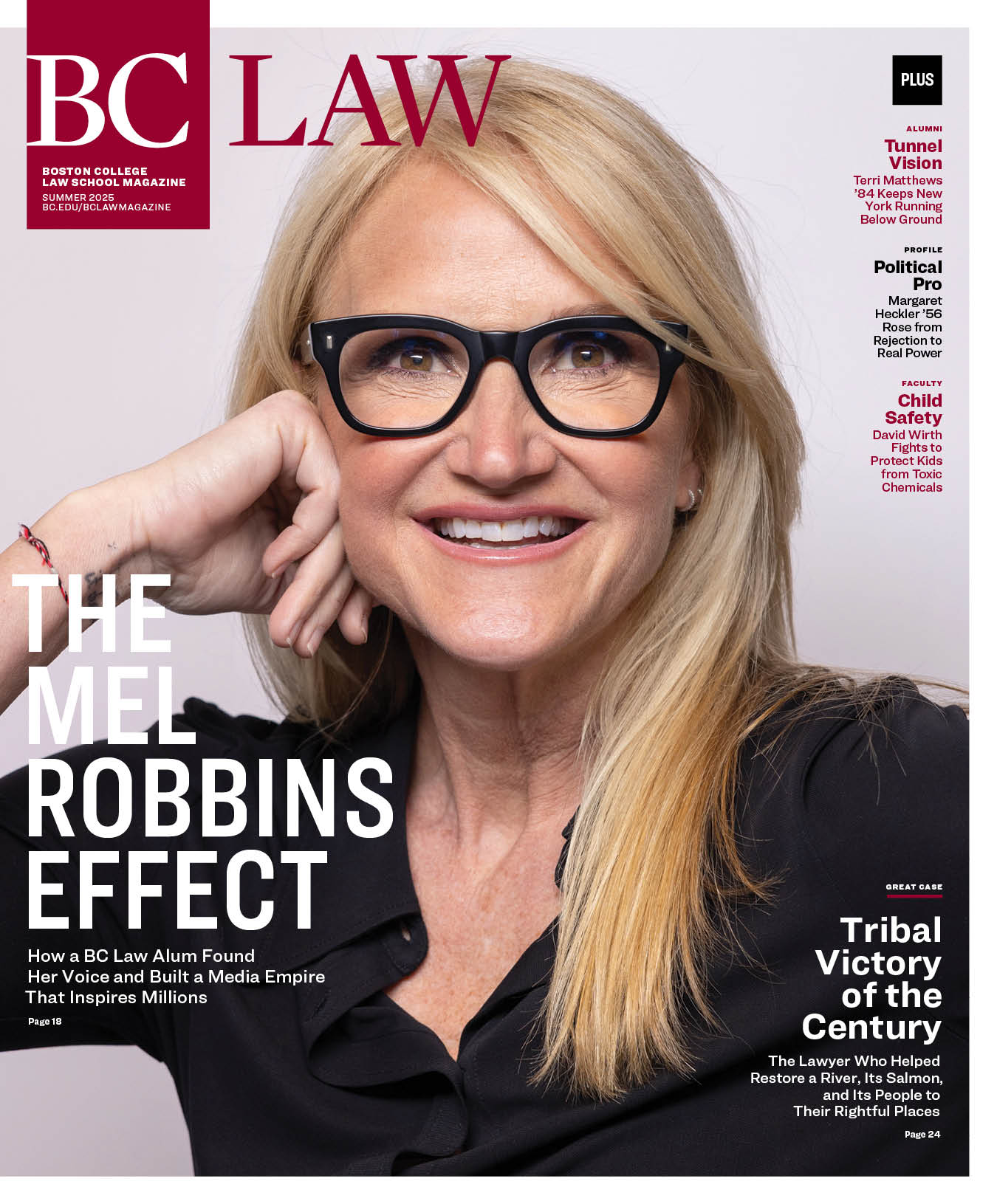

The result of this epiphany is Kimberly Heckler’s A Woman of Firsts: Margaret Heckler, Political Trailblazer (2025, Globe Pequot). The book paints a picture of an intelligent, mission-driven, strategic people-person who knew her own mind and defied categorization. She was a Republican congresswoman from heavily Democratic Massachusetts through the presidencies of LBJ, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan (1967-1983), then Secretary of Health and Human Services (1983-1985) and Ambassador to Ireland (1985-1989). This first book-length chronology of Heckler’s life and times will leave readers wondering why historians, political scientists, and feminist scholars have not studied her with the richness she deserves.

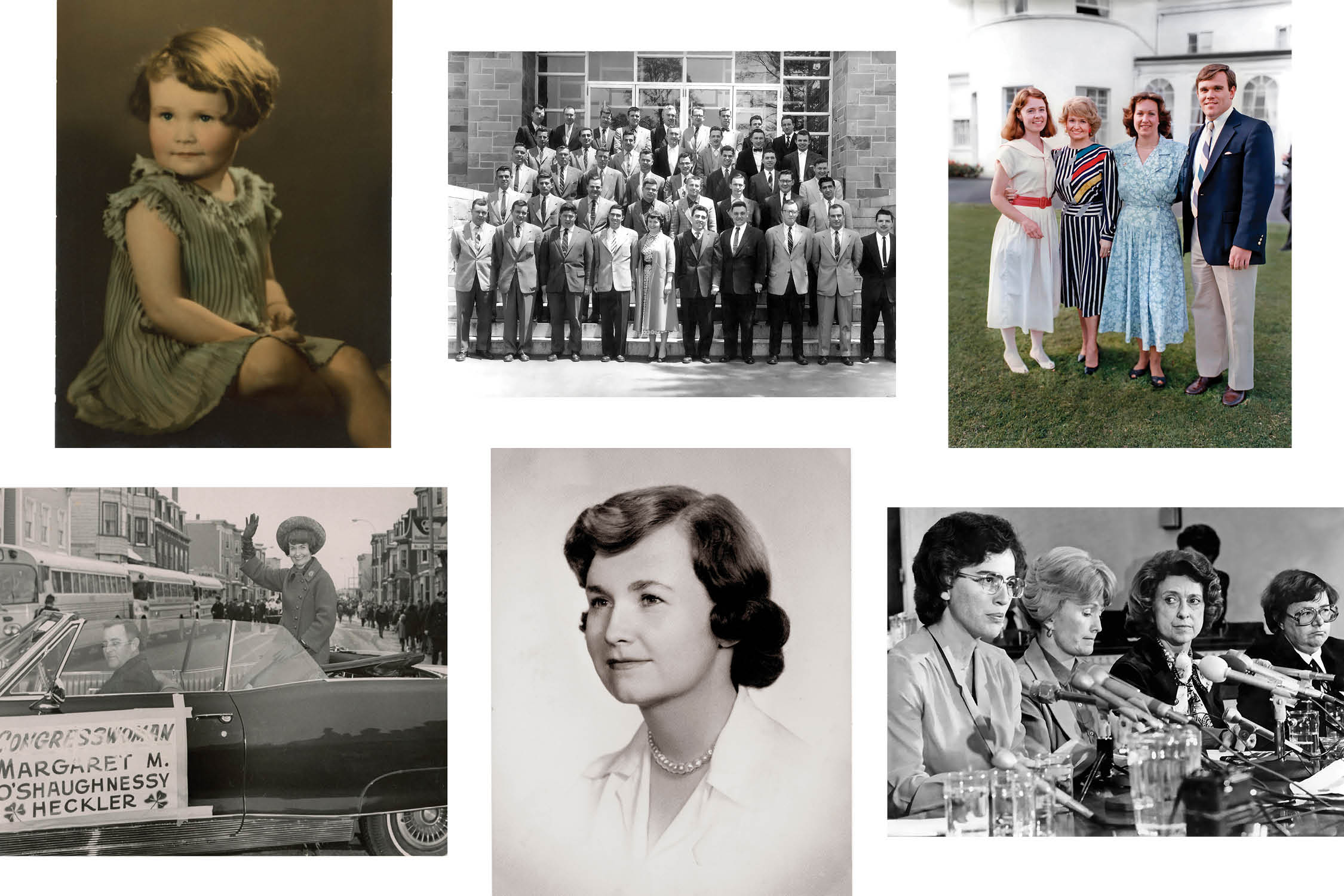

Heckler’s early years were a contradiction of loss and opportunity. Within days of her birth on June 21, 1931, her father, a Manhattan hotel doorman, forced her mother, a private maid, to send Margaret Mary O’Shaughnessy to board in the home of a stranger named Belinda West, a laundress and older widow who lived with her two sisters in the house West owned in Queens, New York. In this female-headed household, West provided for Margaret with the money Heckler’s father’s paid for his daughter’s care, some of which he earned by investing in the stock market on the advice of the wealthy patrons of the hotel where he worked. Heckler’s girlhood included piano lessons and an all-girls Catholic-school education. More than that, Heckler was truly loved by the frugal and generous Belinda West, who groomed her for a cerebral life, and, fortuitously, exposed her to a way of life she may never have seen otherwise.

West was hired by her former laundry customer Grenville Lindall Winthrop, a descendant of the first governor of Massachusetts, to be the caretaker of his Manhattan mansion during the summers of 1938 through 1942, which he spent at his estate in Lenox, Massachusetts. West brought Heckler to stay in the mansion with her, and the impressionable child would drink in Winthrop’s extensive library and collection of four thousand pieces of fine art. Through a church connection, she became a babysitter to the children of Peter T. Farrell, a New York lawyer and state senator, who gave her free range of his law library, encouraged her to attend law school, and gave her a first taste of politics when she campaigned for his successful bid for a county judge’s seat.

Academically gifted and extraordinarily hard-working, Heckler won full scholarships to the elite Manhattan Dominican Academy high school, where she befriended classmates from far more privileged backgrounds, and to Albertus Magnus College in Connecticut, where she majored in political science and economics, met her future husband, John Heckler, with whom she would eventually have three children, and did a summer abroad at the University of Leiden in The Netherlands. She even had a private audience with Pope Pius XII, who, upon hearing of her ambition to attend law school, told her, “Be a lawyer, but serve.” She took this to be a papal blessing.

The only woman in the BC Law Class of 1956, Heckler graduated sixth in the class and briefly engaged in private practice at a time when just 3 percent of American lawyers were women. She then set her sights on politics. The seeds of her political ambitions were planted back in high school, when her dream of being a concert pianist was dashed by her piano teacher, and she stumbled across a book in the public library, How to Go into Politics: A Practical and Entertaining Guide, by Senator Hugh Scott. Reading it helped her tap into the pleasure she felt learning from Judge Farrell and giving speeches on current events at Dominican Academy.

With its 523 men and twelve women, the Ninetieth Congress was rampant with sexism. Yet, in her sixteen years serving, Heckler made her mark passing landmark legislation, traveling to Vietnam and China on fact-finding missions, advancing the welfare of veterans, and co-founding, in 1977, the bipartisan Congresswomen’s Caucus.

In 1962, she ran as a Republican for Massachusetts Governor’s Council and defeated a Democratic male incumbent. The decision to run as a Republican was strategic: her husband thought she’d have a better chance distinguishing herself there than in the crowded, Kennedy-dominated state Democratic party. An indefatigable, personable campaigner, she and her campaign team were resourceful and creative—getting, for example, a local dairy farmer to attach Heckler’s campaign flyers to the glass milk bottles delivered to the doorsteps of homes in her district. At least one voter reported being impressed with the work ethic of a candidate who was up at the crack of dawn to make sure her flyer was on the milk bottle.

In 1966, after two terms on the Governor’s Council, Heckler ran for Congress. The Massachusetts Tenth Congressional District spanned wealthy Wellesley to working-class immigrant Fall River. Against the wishes of establishment (male) Republicans, she challenged eighty-two-year-old Congressman Joe Martin in the primary.

Heckler stumped everywhere, at supermarkets, train stations, Fall River factories, cocktail parties, and on TV. Voters related to her warmth and unthreatening femininity. Sometimes, she toned herself down. On the advice of a friend, she campaigned in a gray wardrobe so she would be taken more seriously (reverting back to bright colors once in Congress on the advice of the same friend so that she would stand out better). Other times, she was tastefully flamboyant, as when she joined the Needham Fourth of July Parade wearing a white suit and red-ribboned hat, while perched on top of a convertible as her volunteers passed out flyers and buttons bearing the slogan, “A Woman’s Place is in the House.” She ultimately won the primary and the general election, all without the backing of big-name Republicans.

With its 523 men and twelve women, the Ninetieth Congress was rampant with sexism. Yet, in her sixteen years serving, Heckler made her mark passing landmark legislation, traveling to Vietnam and China on fact-finding missions, advancing the welfare of veterans, and co-founding, in 1977, the bipartisan Congresswomen’s Caucus.

Her fight for women’s financial equality illustrates so much of what made her effective. In her day, women were blocked from full economic participation. They could not borrow money through loans or credit without a male overseer or cosigner. Heckler herself had been a victim of credit discrimination. In 1957, despite having inherited money from Belinda West’s estate and being a fully employed attorney, Heckler was denied a mortgage when she went to purchase a house in her own name. Nearly two decades later, in Congress, Heckler joined the Banking Committee and authored and sponsored the 1974 Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), which sought to give women the right to credit in their own names and prohibit discrimination against credit applicants on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, or age.

To move the bill out of committee and on to a floor vote, Heckler had to persuade those congressmen who believed that this was a matter for the free market, not the government, as well as Democratic Congresswoman Leonor Sullivan, a committee member and opponent of women’s equality. More broadly, she had to push against the cultural headwinds that denied reality: that 40 percent of women were working and were the breadwinners in 10 percent of all households, and the days of the “so-called little woman who kept her pin money in the sugar bowl,” as she put it to her colleagues, were long gone.

Heckler was tenacious, tactical, and tactful. She assuaged the fears of the CEOs of J.P. Morgan, Chase, Wells Fargo, and other major banks with assurances that the ECOA would still allow them to deny women credit based on their eligibility, same as men. Based on advice from a female Mastercard executive, she galvanized support in the credit industry by arguing that extending credit to women was a business-growth opportunity. She even got Dean Swift, president of the giant company Sears Roebuck, to support the bill. When House Banking Committee member Lindy Boggs (D-LA) tearfully described to the committee how the status quo diminished her life after the sudden death of her husband in a plane crash, the dominoes finally fell. President Ford signed the bill into law on October 28, 1974.

The Reagan administration offered her the position of Secretary of the Treasury. She turned it down. She was then offered to head NASA. She turned that down, too. In the end, she out-maneuvered a man for the job of Secretary of Health and Human Services, where from 1983 to 1985, she took on issues that were unpopular with her party.

To improve the lives of women through legislation, Heckler sought to unite the very disunited women of Congress. Her goal: the creation of a women’s caucus. In 1975, during International Women’s Year, she persuaded a delegation of congresswomen to join her on a trip to China. The trip brought the congresswomen closer. Back in Washington, Heckler capitalized on this by trying to wine and dine her female colleagues into embracing the caucus idea. It didn’t work. But Heckler would not give up. For more than a year, she kept pushing. Finally, New York Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman, a Democrat, agreed to be a co-founder with Heckler of the Congresswomen’s Caucus. Heckler insisted on two simple rules: (1) the Caucus would be co-chaired by one Republican and one Democrat, and (2) its members would move forward only on those issues for which there was unanimity. The upshot was unprecedented legislative progress for women in family leave, pension rights, child support, research funding, domestic and sexual violence, and the Equal Rights Amendment.

Heckler’s devotion to her constituents is credited with her multiple re-elections. But with the rise of Reaganism and the redrawing of her congressional district, she lost her seat in 1982. Unemployed at age fifty-one, she turned to her well-connected friend and former constituent Gerry Abrams for advice. Here’s how Kimberly Heckler describes the encounter in her book:

“Do you know what chutzpah is?” [Abrams] asked her. Margaret nodded as he continued, “It’s the most colossal gall. When you go back to Washington next week for the White House Christmas party and you are in the receiving line…when Reagan bends over to kiss you, pull yourself up from your stockings and whisper in his ear, ‘Mr. President, I supported you and now I need a job!’”

She did exactly that.

Not long after, the Reagan administration offered her the position of Secretary of the Treasury. She turned it down. She was then offered to head NASA. She turned that down, too. In the end, she out-maneuvered a man for the job of Secretary of Health and Human Services, where from 1983 to 1985, she took on issues that were unpopular with her party.

Early in her tenure, several prominent Black physicians made her aware that Black life expectancy was significantly shorter than that of whites. In response, Heckler convened the Task Force on Black and Minority Health. In 1985, the task force released the 600-page, ground-breaking Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health, known to this day as the Heckler Report. It made America’s health disparities unignorable, and led Heckler to create the HHS Office of Minority Health, which pushed for legislation, funding, policy research, and new institutions, community programs, and initiatives.

When AIDS first entered the nation’s consciousness, the public was gripped with fear, the country’s blood bank was threatened, and the Reagan administration looked the other way. Heckler moved forward on her own. In 1983, she made disability benefits available to AIDS victims. She invited the press to publicize her shaking hands with AIDS hospital patients and donating her own blood. She persuaded the White House and congressional Republicans to fund research by showing them why they had a personal stake in understanding the cause of the illness. The resulting studies led to a blood test to detect HIV and made the blood supply safe. Meanwhile, President Reagan did not utter the word “AIDS” in public until 1985.

Heckler’s public life wound down not long after she left HHS. She served as Ambassador to Ireland and left the national stage in 1989. She died in Arlington, Virginia, on August 6, 2018.

To succeed as a moderate Republican in shifting times; to advance women’s equality while eschewing feminist orthodoxy; to champion those marginalized by her own party; to come from nothing and reach greatness: is that destiny? “I feel like a pawn on a chessboard, and I’m a great believer in the Lord’s plan for each of us,” Margaret once said. “When it’s your turn to move, you move.” Sensing when to move, with whom, and how, was Margaret Heckler’s genius.